|

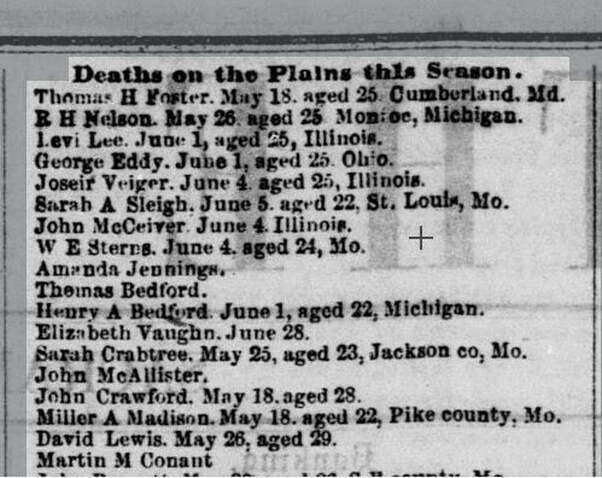

I recently stumbled upon a random newspaper article, “Deaths on the Plains this Season.”[1] Other than the title, the article provides little in the way of detail about why, or how, or from where came the list of names of 250 people who perished as they journeyed to a new life in the west. Nearly all the names are associated with a death date, such as “C.S. Carter, June 5.” Some, like “John Holeman, June 5, age 19” are accompanied by a bit more information, but with “Joseph Langley, age 47,” readers don’t know when he passed.

A man known only as “Battsford” died July 26, “shot by his captain.” T Miller, age 26, was murdered June 15 by R. Tate. But possibly Mr. Tate received his due – “Lafayette Tate, hung June 15, for murder of T. Miller.” M. J. Henderson died the same day. He was from Wisconsin, age 1 year, 2 months and 15 days. The Hardcastles were hit hard in their migration – W. C. died 16 August, age 23; R. P. died, 23 June, age 25; Mrs. D. A. Hardcastle died 6 June, age 26; J. M. Hardcastle died 7 June, age 6; and Mrs. D. J. Hardcastle died 16 June, age 25. Who were these people who shared a surname? Where were they from? Where did they hope to make their new home? A portion of names are associated with locations. Thomas H. Foster who died 18 May at age 25 hailed from Cumberland, Md. R. H. Nelson from Monroe, Michigan died 26 May at age 25. Illinois, Ohio, St. Louis, Pike county Mo., Harvard, Ind., Rarrington, Ohio, and Fairfield, Whoknowswhere all lost sons and daughters who once called those places home. When I first ran across the article I considered how many genealogists who’ve had ancestors “just disappear” have thought about searching newspapers in far-flung locations? Does anyone researching the Baxton family from Ohio City, Ohio wonder what became of G. C. Baxton, born about 1830? He died – somewhere on the plains – 24 June 1852.[2] I tried to find the back story on some of the faceless names from the column, searching 1850 census records to see if I could identify any of those who had a specific location and an age associate with their names. Sadly, I struck out on the handful I investigated. But a Google search led me to David J. Langum’s “Pioneer Justice on the Overland Trails” with more news about two of those 250 deaths in the 1852 newspaper - T. Miller’s and Lafayette Tate.[3] T. Miller, (unnamed in Langum’s article,) was a cattle overseer in the Brown emigrant party who fought with one of the drivers by the name of Tate. The driver's brother, Lafayette Tate, 19, ran up, stabbed Miller in the back, then slit his throat. Based on multiple diary accounts cited by Langum, we learn about the speedy frontier justice – with quickly assembled jury, judge, prosecutor and defense counsel. Witnesses were examined, Tate was found guilty and thirty minutes later hanged. According to the diaries Langum cited, the brother who originally fought with Miller was allowed to continue on with the company. For those interested in more about pioneer justice on the trails, be sure to read Langum’s article. But even for those whose relatives might have disappeared in a less dramatic fashion, I hope this post might inspire researchers to not stop at just the local paper in their ancestral locations, but consult even far-off papers for details on their families’ lives. [1] “Deaths on the Plains this Season,” Sacramento Daily Union, 2 November 1852, p. 2, col. 5; digital image, California Digital Newspaper Collection (www.cdnc.ucr.edu : accessed 7 July 2020). A search on The California Digital Newspaper Collection for “death on the plains” led to other articles in Sacramento and San Francisco newspapers, some of which were repeats of each other. [2] “Death on the Plains this Season.” [3] Langum, David J. "Pioneer Justice on the Overland Trails." The Western Historical Quarterly 5, no. 4 (1974): 421-39. Accessed July 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/967307.

2 Comments

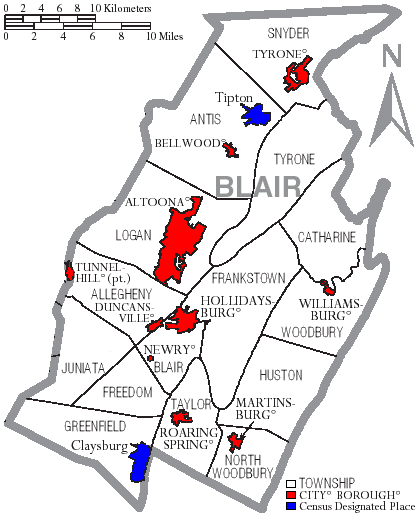

Map of Blair County Pennsylvania With Municipal and Township Labels - from Wikimedia Commons Map of Blair County Pennsylvania With Municipal and Township Labels - from Wikimedia Commons ProGen is a study group to encourage professional and aspiring genealogists.[1] Each month, participants read sections of Professional Genealogy: Preparation, Practice and Standards[2] and Genealogy Standards.[3] In conjunction with the readings, they write up an assignment, and review the work of their fellow students, offering constructive comments. Each month, students meet online in an hour-long discussion about the readings or assignment. The strength of the program is the peer-feedback. I described it to someone recently as “the ultimate pyramid scheme” – but in a really really good way! Think about it. You read a chapter and write up an assignment. Then you turn in your assignment and you get to see seven other people’s take on the same assignment! They give you feedback on your work – a great benefit. But even better is you get the chance to analyze their work. You think about “Why did they include that?” “Will I include that when I do something like that in the future?” “Does one format work better than another for this kind of product?” “Paragraphs or bullet points?” “Hyperlinks – yes or no?” “How would I approach my colleague’s problem?” And then, you get to read each other’s feedback on the other assignments. “Hmmm… I didn’t even notice that thing that he pointed out… I’ll have to look out for that in the future.” There is learning on so many levels in this kind of a peer-feedback environment – when you write your own work, get critiques on your own work, mentally analyze someone else’s work, formulate useful coherent comments on other’s work, and read the analyses of other people on the same work. As I said, I now have the chance to mentor a group of ProGen students. This month their assignment was to write a locality guide. As a group they’ve turned in guides for Italy, Ireland, Belarus, Connecticut, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Oregon, Indiana and more – sometimes at a county level, sometimes at a state level. Each one of these I read has resources I’ve never seen. While I might not have ancestors in each specific locality, I can learn about types of records and strategies from each of them. “Hmm… Franklin County, Pennsylvania has xyz? Does Blair County where my people lived have those same kind of records? I’ll have to look for those!” I did many of the same assignments when I was a student in ProGen four years ago. But I’ve decided that I’m going to do the same assignments as the students in my group are doing. I’m in the thick of some research on my Bradley family – my great-grandfather Peter Bradley (1808-1861) and his nine siblings – five brothers and four sisters – at least eight of whom emigrated from County Tyrone, Ireland and settled in several counties in western Pennsylvania between about 1830 and 1850. I think a locality guide for each of these counties will help me to understand more about my Bradleys. For a link to my locality guide for Blair County, Pennsylvania, click here. [1] ProGen Study Groups (https://www.progenstudy.org/). [2] Elizabeth Shown Mills, CG, CGL, FASG, ed. Professional Genealogy: Preparation, Practice & Standards (Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2018). [3] Board for Certification of Genealogists, Genealogy Standards, 2nd ed. (Nashville, Tennessee: Ancestry.com, 2019). |

AuthorMary Kircher Roddy is a genealogist, writer and lecturer, always looking for the story. Her blog is a combination of the stories she has found and the tools she used to find them. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|