|

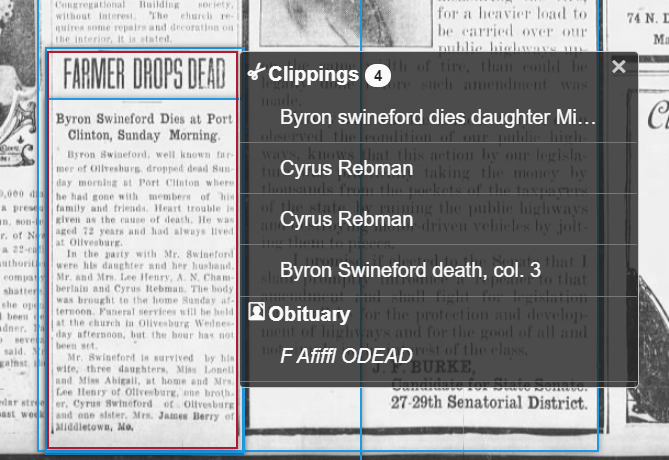

When you clip something from a newspaper on Newspapers.com, are you looking to see whether anyone else has clipped the same item? There are a couple of reasons why you might want to… When you clip something on Newspapers.com, it saves it and makes a little notation that looks like this: ( This is one I clipped a couple of weeks ago. (You can see my Newspapers.com “handle.”) The clipping is an obituary for Byron Swineford of Olivesburg, Richland County, Ohio. But if anyone looks at the thing I clipped on that newspaper page on Newspapers.com and hovers their cursor over the article, a feature pops up showing that other people have also clipped that same article. This article has been clipped four times. The bottom one is what I called it when I clipped it. Who are those other clippers who are interested in Byron Swineford? When I click on the top one, I can get a different pop-up: (I have blocked out their name for privacy reasons and renamed them ResearcherX) If I click on the “View Clipping” button, I get this: (Again, blocked out name and changed to ResearcherX.) I can see that they clipped that article on 20 October 2018. Now, if I click on ResearcherX’s name, Newspapers.com takes me to their profile page. Why is this of interest to me? I clipped that article on Byron Swineford because he’s a distant relative. And my guess is that ResearcherX clipped it for the same reason. I can scroll through all of ResearcherX’s clippings, because maybe there are other articles they clipped that are also about relatives of mine. Depending on how many they have, I might scroll through all ResearcherX’s clippings. But there are probably a lot of things they clipped that aren’t about my relatives. But I definitely want to look at what else they clipped on 20 October 2018, the same day they clipped my Byron Swineford article. Let me go do that. [Okay…. Do you know how much time it’s taken me to get to this next paragraph? A lot! Because ResearcherX is a prolific clipper! Man! So. Much. Stuff. But I digress…] But what was ResearcherX doing on 20 October 2018? They were busy snagging 20 - count ‘em 20! - articles, mostly about the Swineford family. This is just the kind of content I’m looking for. For example, one of those 20 clippings was about the will of Israel Swineford, Byron’s father. If I didn’t already know who Byron Swineford’s father was, I sure do now! Like many genealogists, Researcherx digs deep on a given day or in a given week, into whoever their subject of the moment is, gathering all the content they can find about their person of interest and their FAN club. And those are exactly the same people I’m interested in. ResearcherX and I are obviously interested in Byron and Israel, and I can use their breadcrumb trail of newspaper clippings to learn about those same people and their associates. Sniffing around ResearcherX’s content, I may be able to discern how we are connected. I can even decide that ResearcherX knows enough about our common family that I can click on the button on their Newspapers.com profile page to follow them to see what other interesting content they come up with. If I put on my detective hat, I may be able to find out ResearcherX's real name and see if they want to collaborate on research. So many possibilities, just because I wondered who else is clipping the same stuff I'm clipping. So when you find someone else has clipped the same article you clip, be sure to follow their breadcrumbs to find more clues for your own research.

4 Comments

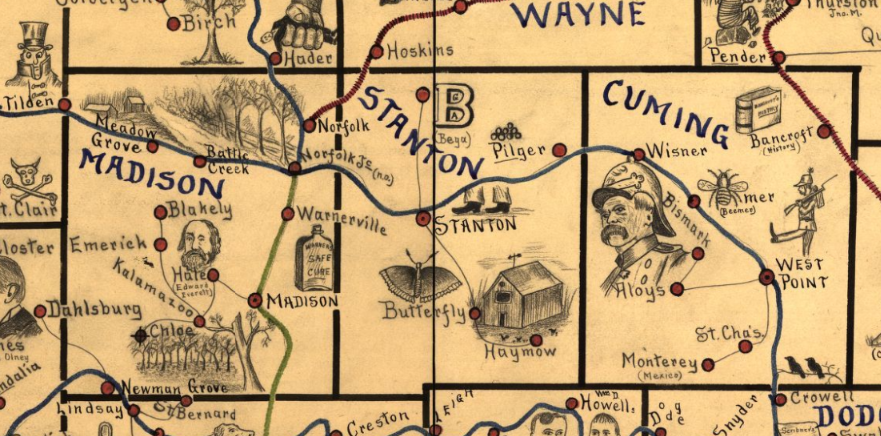

My granddaughter came to visit a few weeks ago. We played endless games of Splash! – basically the old card game of Spoons, only with squeaky rubber dolphins instead of kitchen cutlery. She wanted to collect all the dolphins, though sometimes she would generously share one or two with me. And after each game, Grandma had to “shovel” the cards. (That skill I learned around my own childhood card games, “bridges,” is a source of continuing amusement to the next generation.) Why is Splash! with my granddaughter fodder for my genealogy blog? It’s the way she directed my activity – I was to “shovel” the cards. Yes, of course she meant shuffle, but she’s almost four and can’t quite spell, and is still learning pronunciation. She heard and expressed the “F” as a “V,” a natural leap. When I was a baby genealogist, in order to find my ancestors in census records, needed to use a Soundex calculator. Soundex sorts the consonants in the English language into one of six groups.[1] For example “F” and “V” are also grouped with “P” and “B.” The sounds these letters make emanate from the same part of the mouth with the lips and tongue in a similar position. That’s why they sound alike. And can be easily confused. So take a lesson from my granddaughter. When you’re looking for your “Baresh” ancestors in newspapers or census records, think about searching for “Parish” records as well. And if you’re looking for “Lefflers” and “Fellers” look for “Levelers” and “Vellers,” too. [1] Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org), "Soundex" rev. 15:03, 3 April 2021. Today when I was trying to find a 1900-1910 railroad map of Nebraska, I ran across the one of the most charming maps I’ve ever seen.

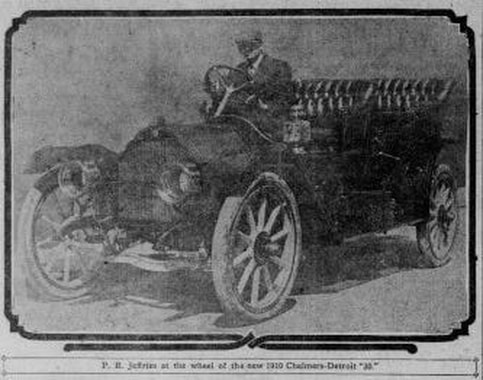

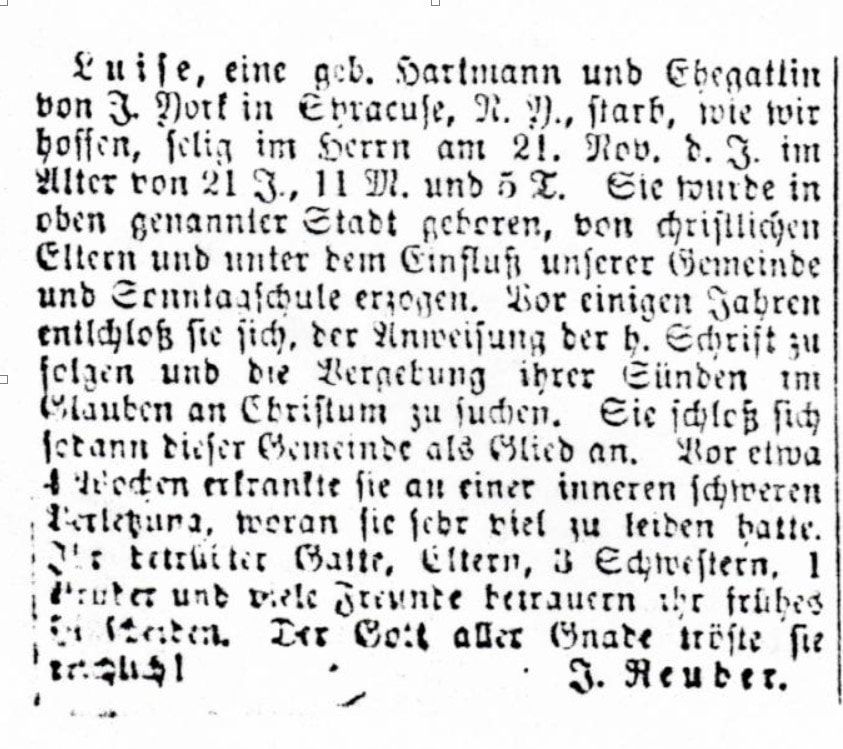

In the late 19th century, Frank Galbraith, a railway mail clerk, created a set of mnemonic maps to aid railway clerks studying for Civil Service examinations. These clerks had to be able to sort mail for distribution to post offices across the US. They needed to know which rail lines serve each of the thousands of post offices, so a clerk could get the right letter on the right train. Can you imagine a railway mail clerk trying to learn the name and location of every town simply from a list of names. Yeah, the big places you know – Omaha and Lincoln. Some other crossroads towns you probably know, like York or Columbus. But Roten? Where the heck is that? Or Campbell or Franklin or Stockham, or any of scores of unconnected, random names that you just had to memorize what the name was, where it was on a map, and what railroad lines would serve that place. Boring! And hard! Names of random towns are just strings of characters, indistinguishable one from another. But the clever Frank Galbraith had a plan. He created single-purpose maps, just meant for railway clerks. They didn’t show all the geographic features such as rivers and lakes. What Galbraith focused on was “spatial proximity of place name to railroad route. His maps were hand-drawn and illustrated with images meant to represent a place name.”[1] For instance once section of the Nebraska map identifying post offices in Adams and Webster counties has images including a sailing ship, a copy, a range of 3 hills, a pair of cows, and a curve-bladed knife, representing Mayflower, Holstein, Blue Hill (yes, the hills are rendered in blue pencil), Cowles, and Bladen. In the county west of Webster, the town which shares its name with the county is represented by a sketch of the familiar founding father Franklin (Ben), while another local town, Campbell is illustrated with a camel. References to many of the images, which represented familiar faces in the late 19th century political landscape, have been lost to history. For instance, the illustration for Tilden, a town straddling the border between Madison and Antelope counties, is represented by the top-hatted Samuel J. Tilden, New York Governor and 1876 presidential candidate who lost to Rutherford B. Hayes in a contested election. The maps display much of the racial stereotypes of the time they were created. Anti African-American and anti-Asian prejudice are evident in many of the images. So too is patriotic imagery with American flags being used frequently in the maps. Virgina Mason’t article referenced in Footnote 1 below gives an in-depth history of the maps and great explanations on their symbols. You can find these charming maps on the Library of Congress website. The collection includes maps of eight states - Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri and Nebraska. Check out the link here https://www.loc.gov/search/?in=&q=galbraith+railway&new=true. When you’ve had a chance to explore, check out Humboldt, Richardson County, Nebraska. I just love the sense of whimsy in that town’s icon. Please share some of your favorite town pictures with me in the comments. [1] Virginia W. Mason, “Frank H .Galbraith’s Railway Service Maps,” Cartographic Perspectives, no. 41, Winter 2002, p. 24-43; https://cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/view/cp41-mason.  Undated newspaper clipping sent by my father's cousin Thelma VanAlstyne with Kircher and Springer family papers Undated newspaper clipping sent by my father's cousin Thelma VanAlstyne with Kircher and Springer family papers I had the most wonderful experience yesterday at the Virtual Genealogical Association’s conference. I’ve been fortunate in the last five years or so to be selected to present at conferences and to genealogy societies about my favorite topic. I’ve gotten to meet some very nice people. I’ve learned more about my own family as I’ve tried to come up with examples to demonstrate a technique or website. I’ve made a little bit of money to spend on my genealogical addiction. But my favorite part is having a captive audience who might have an answer to one of my own questions. Yesterday I presented “Fraktur und Fremdwörter: Hacks for Reading Foreign Books & Newspapers” at the VGA conference. I had a chance to demonstrate how a hopelessly English-only reader can find an old German fraktur font newspaper article about their ancestor and easily, painlessly, and in only a few minutes, translate it into something they can read. I demonstrated the how-tos for all my favorite newspaper sites. In addition to finding newspaper articles on websites, I think genealogists often have snippets of things in their family papers – perhaps an article pasted into a scrapbook. I have one such article from my Dad’s cousin Thelma with the notation “Translation? Appears it concerns Louise Hartman, Syracuse, N.Y.” I played around with finding a way to scan that article and convert it to OCR. None were terribly effective. In my presentation, I showed my unsuccessful attempts with the caveat, “Sorry folks, on this kind of an item, you just might need to buck up and try to transcribe that article yourself. Unless…. If anyone knows some better way, I’d love to hear about it.” And in that captive audience, Mr. Miles Meyer piped up (in the chat box) and suggested NewOCR.com. From their website: NewOCR is a ”free online OCR (Optical Character Recognition) service, can analyze the text in any image file that you upload, and then convert the text from the image into text that you can easily edit on your computer.” I’ll post again in the next few days about my attempts to transcribe my scrapbook article with my new-found tool. But in the meantime, thank you Miles, thank you Katherine Willson, Dan Earl, Linda Debe and the rest of the people at the Virtual Genealogical Association for putting on a great conference. If you’re interested, check them out. You might be able to be able to catch up on the recordings of the great sessions they have offered at their second virtual conference. If you’re anything like me, you want to know simply everything about your ancestors. I have fantasies about getting to heaven and being able to talk with my great-great grandmother about the color of the wallpaper in the upstairs back bedroom in her house! And recently I found a resource containing an unusual list. City directories are great for locating where our ancestors were between census years. We can search directories by name to plot year by year where our ancestors were living. We can search them by address, to see who else might have been living with them – I’ve found women’s maiden names when I discovered their parents in the same house at the same time. And many directories are filled with lists – lists of churches, fraternal organizations, funeral homes, cemeteries and more that our ancestors might have been involved with or used. But one list I saw in a directory blew me away. How would you like to find something like the “Automobile Directory of Montgomery County, [Illinois]”?! From a 1918 directory I learned that Clem Bedinghaus on Rt. 1 in Farmersville owned an Overland. John Carroll from Ramsey owned a Hupmobile. Roscoe Heim of Harvel drove a Dort. (I’ll resist the temptation to tell you all about the four models Dort offered for sale. You’re a good researcher, and I’m sure you can find the info if I have piqued your interest….) Arthur Greenwood drove a Briscoe, John Hucker a Crow Elkhart and William Herzog a Paige. (Are you still with me or have I lost you to the early 20th century automobile section of Wikipedia?) Ed. Lessman owned two automobiles – a Ford and a Buick.[1] Explore city directories. You can find them on some of the genealogy websites and also on more general sites like GoogleBooks and Archive.org. But don’t just look for your ancestor’s name and address. Browse through all the pages to see what made their hometown the special place at was to them. [1] Prairie Farmer’s Directory of Montgomery County, Illinois, (Chicago: Prairie Farmer Publishing, 1918); digital images, Archive.org (archive.org : accessed 7 July 2020). The assignment for my ProGen group this month is to transcribe and abstract a document, and create a research plan to try to answer a self-created research question arising from information contained in the document. Suggested document types for this assignment include wills and deeds.

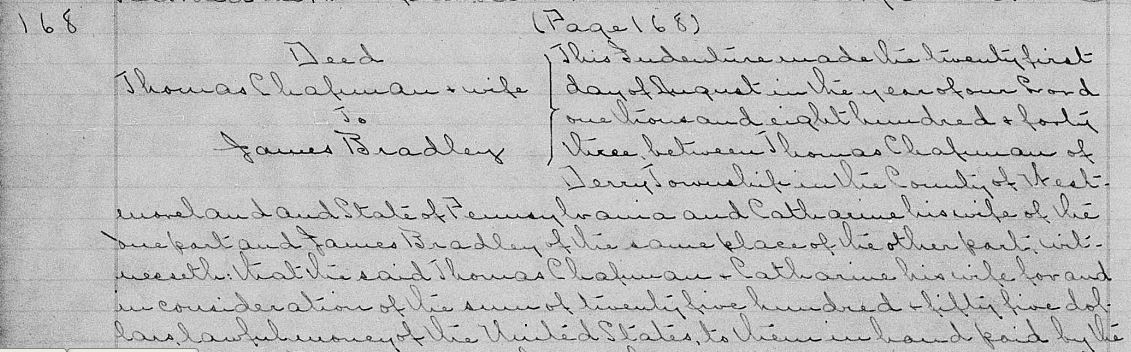

As a ProGen mentor, I’ve decided I will do the same or similar tasks as my mentees are doing. I transcribed three deeds from Westmoreland County. Interestingly, out of 24 participants in my ProGen groups, only three chose deeds, and all the rest worked on wills. I’m looking forward to meeting with them today, and maybe hearing a bit about why they selected the document they used. In addition to the transcription and abstract, the ProGen assignment included creating a research plan. The deeds I transcribed are part of a larger piece of research I’m doing on my Bradley family who emigrated from County Tyrone to several counties in western Pennsylvania. Because of this, I opted not to do the research plan part of the assignment. But it was good practice for me to create the transcriptions and abstracts. Here is my abstract of one deed in which James Bradley purchased land from Thomas Chapman. You can see the deed yourself on FamilySearch by following my citation in the footnotes. Chapman to Bradley, Warranty Deed Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania Deed Book 27, p 168 Drawn 21 August 1843; recorded 13 September, 1843 21 August 1843, Thomas Chapman and Catherine his wife of Derry Township, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, for twenty five hundred & fifty five dollars paid by James Bradley of the same place sell land in Derry Township described as follows: Beginning at a post, at a corner of Jacob Walter’s lands thence by lands of Samuel Morehead, north seventy & three fourth degrees west one hundred and seventy nine perches to a white oak stump, north sixty three degrees west, sixty and one perches to a post, thence by land of Daniel Dunlap , north thirty seven and one fourth degrees east, forty three perches to a post, thence by other lands of said Thomas Chapman (of which this is a part) north seventy nine degrees east one hundred and eighty seven and six tenths perches to a post, north forty five degrees east, eighteen and two tenths perches to a white oak, south eighty one degrees east five and three tenth perches to a post, thence by land of Hardy Sloan, south one and one half degrees west, one hundred & thirty three perches to a post, thence by lands of Jacob Walters north south fifty two degrees west sixteen & three tenth perches to a post, and thence south twenty four degrees east twenty eight perches to a post the place of beginning: containing one hundred and twenty seven and three fourth acres and allowance [It being a part of a tract containing three hundred and twelve acres surveyed to Joseph Armstrong on application No 2180 dated third of May 1769. Thomas Chapman and Catherine will warrant and forever defend, against all and every other person or persons whomsoever, lawfully claiming or to claim the same or any part thereof, except the claims of the Commonwealth. [Signed] Thomas Chapman & Catharine Chapman Witnesses: Elizabeth Davis, Stewart Davis, Felix Bradley 21 August 1843, property delivered by Chapman and Catherine to Bradley, in presence of Stewart Davis 12 September 1843, acknowledgement by Chapman and dower release by Catherine.[1] What I still need to do with this deed:

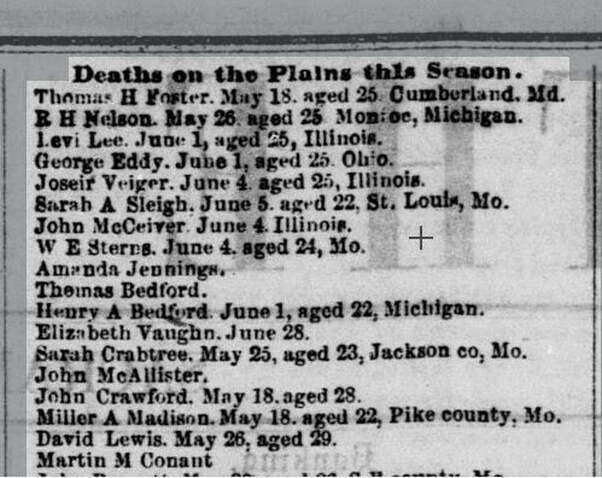

I have a bit more work to do on this project, but I feel like I've made a good stard. [1] Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, Deed Book 27:168, Thomas Chapman et ux to James Bradley, 21 August 1843; Westmoreland County Clerk's Office, Greensburg; digital images, FamilySearch (www.familysearch : accessed 21 July 2020) > United States, Pennsylvania, Westmoreland > Deeds, 1773-1886; Index > Deeds, v. 27, Apr 1843 - Dec 1844 > images 588-9 of 895). [2] Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, Deed Book 37:456, James Bradly to Phelix Bradly, 22 March 1855; Westmoreland County Clerk's Office, Greensburg; digital images, FamilySearch (www.familysearch : accessed 21 July 2020) > United States, Pennsylvania, Westmoreland > Deeds, 1773-1886; Index > Deeds, v. 37 (p.1-568), Aug 1854 - May 1855 > image 684 of 756. [3] Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, Deed Book 79:371-3, James Bradley to Mary Bradly, 3 September 1873; Westmoreland County Clerk's Office, Greensburg; digital images, FamilySearch (www.familysearch : accessed 21 July 2020) > United States, Pennsylvania, Westmoreland > Deeds, 1773-1886; Index > Deeds, v. 79, Oct 1873 - Apr 1874 > images 552-3 of 709). I recently stumbled upon a random newspaper article, “Deaths on the Plains this Season.”[1] Other than the title, the article provides little in the way of detail about why, or how, or from where came the list of names of 250 people who perished as they journeyed to a new life in the west. Nearly all the names are associated with a death date, such as “C.S. Carter, June 5.” Some, like “John Holeman, June 5, age 19” are accompanied by a bit more information, but with “Joseph Langley, age 47,” readers don’t know when he passed.

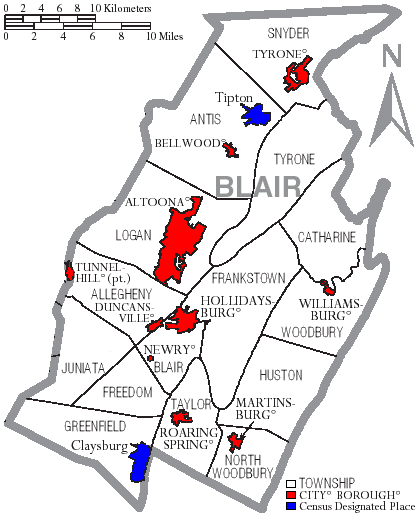

A man known only as “Battsford” died July 26, “shot by his captain.” T Miller, age 26, was murdered June 15 by R. Tate. But possibly Mr. Tate received his due – “Lafayette Tate, hung June 15, for murder of T. Miller.” M. J. Henderson died the same day. He was from Wisconsin, age 1 year, 2 months and 15 days. The Hardcastles were hit hard in their migration – W. C. died 16 August, age 23; R. P. died, 23 June, age 25; Mrs. D. A. Hardcastle died 6 June, age 26; J. M. Hardcastle died 7 June, age 6; and Mrs. D. J. Hardcastle died 16 June, age 25. Who were these people who shared a surname? Where were they from? Where did they hope to make their new home? A portion of names are associated with locations. Thomas H. Foster who died 18 May at age 25 hailed from Cumberland, Md. R. H. Nelson from Monroe, Michigan died 26 May at age 25. Illinois, Ohio, St. Louis, Pike county Mo., Harvard, Ind., Rarrington, Ohio, and Fairfield, Whoknowswhere all lost sons and daughters who once called those places home. When I first ran across the article I considered how many genealogists who’ve had ancestors “just disappear” have thought about searching newspapers in far-flung locations? Does anyone researching the Baxton family from Ohio City, Ohio wonder what became of G. C. Baxton, born about 1830? He died – somewhere on the plains – 24 June 1852.[2] I tried to find the back story on some of the faceless names from the column, searching 1850 census records to see if I could identify any of those who had a specific location and an age associate with their names. Sadly, I struck out on the handful I investigated. But a Google search led me to David J. Langum’s “Pioneer Justice on the Overland Trails” with more news about two of those 250 deaths in the 1852 newspaper - T. Miller’s and Lafayette Tate.[3] T. Miller, (unnamed in Langum’s article,) was a cattle overseer in the Brown emigrant party who fought with one of the drivers by the name of Tate. The driver's brother, Lafayette Tate, 19, ran up, stabbed Miller in the back, then slit his throat. Based on multiple diary accounts cited by Langum, we learn about the speedy frontier justice – with quickly assembled jury, judge, prosecutor and defense counsel. Witnesses were examined, Tate was found guilty and thirty minutes later hanged. According to the diaries Langum cited, the brother who originally fought with Miller was allowed to continue on with the company. For those interested in more about pioneer justice on the trails, be sure to read Langum’s article. But even for those whose relatives might have disappeared in a less dramatic fashion, I hope this post might inspire researchers to not stop at just the local paper in their ancestral locations, but consult even far-off papers for details on their families’ lives. [1] “Deaths on the Plains this Season,” Sacramento Daily Union, 2 November 1852, p. 2, col. 5; digital image, California Digital Newspaper Collection (www.cdnc.ucr.edu : accessed 7 July 2020). A search on The California Digital Newspaper Collection for “death on the plains” led to other articles in Sacramento and San Francisco newspapers, some of which were repeats of each other. [2] “Death on the Plains this Season.” [3] Langum, David J. "Pioneer Justice on the Overland Trails." The Western Historical Quarterly 5, no. 4 (1974): 421-39. Accessed July 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/967307.  Map of Blair County Pennsylvania With Municipal and Township Labels - from Wikimedia Commons Map of Blair County Pennsylvania With Municipal and Township Labels - from Wikimedia Commons ProGen is a study group to encourage professional and aspiring genealogists.[1] Each month, participants read sections of Professional Genealogy: Preparation, Practice and Standards[2] and Genealogy Standards.[3] In conjunction with the readings, they write up an assignment, and review the work of their fellow students, offering constructive comments. Each month, students meet online in an hour-long discussion about the readings or assignment. The strength of the program is the peer-feedback. I described it to someone recently as “the ultimate pyramid scheme” – but in a really really good way! Think about it. You read a chapter and write up an assignment. Then you turn in your assignment and you get to see seven other people’s take on the same assignment! They give you feedback on your work – a great benefit. But even better is you get the chance to analyze their work. You think about “Why did they include that?” “Will I include that when I do something like that in the future?” “Does one format work better than another for this kind of product?” “Paragraphs or bullet points?” “Hyperlinks – yes or no?” “How would I approach my colleague’s problem?” And then, you get to read each other’s feedback on the other assignments. “Hmmm… I didn’t even notice that thing that he pointed out… I’ll have to look out for that in the future.” There is learning on so many levels in this kind of a peer-feedback environment – when you write your own work, get critiques on your own work, mentally analyze someone else’s work, formulate useful coherent comments on other’s work, and read the analyses of other people on the same work. As I said, I now have the chance to mentor a group of ProGen students. This month their assignment was to write a locality guide. As a group they’ve turned in guides for Italy, Ireland, Belarus, Connecticut, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Oregon, Indiana and more – sometimes at a county level, sometimes at a state level. Each one of these I read has resources I’ve never seen. While I might not have ancestors in each specific locality, I can learn about types of records and strategies from each of them. “Hmm… Franklin County, Pennsylvania has xyz? Does Blair County where my people lived have those same kind of records? I’ll have to look for those!” I did many of the same assignments when I was a student in ProGen four years ago. But I’ve decided that I’m going to do the same assignments as the students in my group are doing. I’m in the thick of some research on my Bradley family – my great-grandfather Peter Bradley (1808-1861) and his nine siblings – five brothers and four sisters – at least eight of whom emigrated from County Tyrone, Ireland and settled in several counties in western Pennsylvania between about 1830 and 1850. I think a locality guide for each of these counties will help me to understand more about my Bradleys. For a link to my locality guide for Blair County, Pennsylvania, click here. [1] ProGen Study Groups (https://www.progenstudy.org/). [2] Elizabeth Shown Mills, CG, CGL, FASG, ed. Professional Genealogy: Preparation, Practice & Standards (Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2018). [3] Board for Certification of Genealogists, Genealogy Standards, 2nd ed. (Nashville, Tennessee: Ancestry.com, 2019).  František Dvořák - Mother with a Child, Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/ : accessed 21 Feb 2020) František Dvořák - Mother with a Child, Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/ : accessed 21 Feb 2020) I ran across a newspaper item this morning while looking for my family. I don’t have any reason to believe the article specifically refers to anyone I know, but the tale is timeless… A new-born babe was left on the door-step of a house in Boston, with this touching note: - ‘To the tender mercies of this cold and wicked world this little infant is committed. – Whoever receives it, cares for it, and adopts it, may yet live to bless the day that thus their kindness has been bestowed. Born of a victim of misplaced confidence, yet the heart and affection of the mother never die.’”1] It just made me think of the many cases of unknown parentage I have worked to solve. The heartbreak of the mother, that victim of misplaced confidence, is palpable. I hope the child was loved. [1] Untitled, The Altoona Tribune (Altoona, Pennsylvania), p. 2, col. 5; digital image, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/image/278498074 : accessed 21 Feb 2020). A lot of genealogists read the good stuff, scholarly journals such as the National Genealogical Society Quarterly and The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. They are both great publications, and you’ll see many examples of well-written case studies and compiled genealogies. In them you will see example after example of precise, efficient citations. The articles have undergone multiple levels of review that have cleaned up mistakes and filled in gaps in research.

I know from personal experience that an article I submitted to “The Q” had holes in my research, things I hadn’t addressed. And my first round of citations was something I am currently less than proud of. But the editors saw potential and worked with me to fix the text and citations so they would meet the publications standard, and hopefully be an example to other genealogists. When you read an article in The Q, you’ll look at the citations to see what kind of resources the author consulted. You might even go look at some of those specific references yourself, and in so doing perhaps learn about a valuable resource you haven’t thought about using in your own research. Those are good lessons. But what you won’t see between the covers of those hallowed periodicals are the crappy citations that don’t really document what they say they do. There’s plenty of sloppy citations out there. You probably have some in your own writing. I know I do. I’m sure your friends do, too. Somebody might write a citation to the gravestone of Charles Kircher on his FindAGrave memorial in Marin County, California and say that he was born 25 April 1879.[1] The gravestone does not have the birthdate. It has a year, but not the actual date. (And until sometime after his wife died in 1968, Charles’ stone didn’t even have the years of his life span on the stone![2]) So, no, that stone does not tell you he was born 25 April 1879. The memorial does, but what made the memorial poster make the leap from the simple 1879 that the stone says to a specific date? So that’s something you ought to dig a little more into if you want to be thorough. Somebody knew (or thought they knew) something about the actual date. You’ve got a clue now – can you prove it? Another example – 1870 census. You know that man is your great-great grandfather, and that woman is his wife, and those three children are all their sons and daughters. Because you know the family. So you say that Fred and Wilma’s children were A, B, and C, and you cite as your source the 1870 census. But the 1870 census does not state relationships. Those people could be five random strangers who share similar names to your family. You need think about and understand what that record says, and what it doesn’t say. And you need to be precise in writing your text and your citations so you reflect that analysis and understanding. These examples of imprecision in writing are likely to be dealt with before they hit the pages of the lofty journals we read. But imprecision is present in all our writing. If you’re willing to pass your pages on to a trusted friend for review, and return the favor by reviewing theirs, you’ll begin to see how to improve your precision in your writing and your citations. They’ll call you on your mistakes, you’ll call them on theirs, and the next time around you’ll think before you make those same imprecise assertions. Read a little bad writing. It’ll make you a better genealogist! [1] Find A Grave, (http://findagrave.com : accessed 9 February 2020), memorial 59231349, Charles Arthur Kircher (1879-1952), and digital image of Mount Olivet Catholic Cemetery (San Rafael, Marin, California, Charles Kircher gravestone; memorial contributed by Carl Bennett 26 September 2010 and gravestone photo contributed by “FosterFamilyTree, date unknown. [2] Charles and Agnes are my paternal grandparents. My dad told me that, even though Charlie and Agnes used to enjoy taking picnics to random cemeteries and had a grand old time mentally recreating the lives represented by the names and dates etched in those granite markers, when Charlie died, Agnes had nothing but his name put on his gravestone. Their daughter Mary waited patiently for another 14 years, and when Agnes died in 1968, Mary had Agnes’ name and years put on her stone, and amended Charlie’s to get his years, too. |

AuthorMary Kircher Roddy is a genealogist, writer and lecturer, always looking for the story. Her blog is a combination of the stories she has found and the tools she used to find them. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|