|

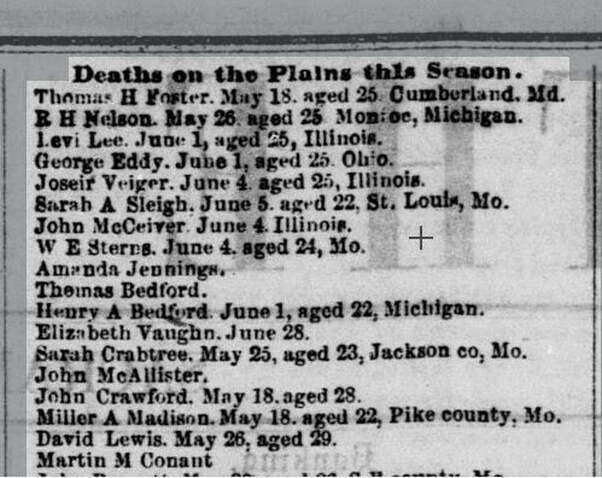

I recently stumbled upon a random newspaper article, “Deaths on the Plains this Season.”[1] Other than the title, the article provides little in the way of detail about why, or how, or from where came the list of names of 250 people who perished as they journeyed to a new life in the west. Nearly all the names are associated with a death date, such as “C.S. Carter, June 5.” Some, like “John Holeman, June 5, age 19” are accompanied by a bit more information, but with “Joseph Langley, age 47,” readers don’t know when he passed.

A man known only as “Battsford” died July 26, “shot by his captain.” T Miller, age 26, was murdered June 15 by R. Tate. But possibly Mr. Tate received his due – “Lafayette Tate, hung June 15, for murder of T. Miller.” M. J. Henderson died the same day. He was from Wisconsin, age 1 year, 2 months and 15 days. The Hardcastles were hit hard in their migration – W. C. died 16 August, age 23; R. P. died, 23 June, age 25; Mrs. D. A. Hardcastle died 6 June, age 26; J. M. Hardcastle died 7 June, age 6; and Mrs. D. J. Hardcastle died 16 June, age 25. Who were these people who shared a surname? Where were they from? Where did they hope to make their new home? A portion of names are associated with locations. Thomas H. Foster who died 18 May at age 25 hailed from Cumberland, Md. R. H. Nelson from Monroe, Michigan died 26 May at age 25. Illinois, Ohio, St. Louis, Pike county Mo., Harvard, Ind., Rarrington, Ohio, and Fairfield, Whoknowswhere all lost sons and daughters who once called those places home. When I first ran across the article I considered how many genealogists who’ve had ancestors “just disappear” have thought about searching newspapers in far-flung locations? Does anyone researching the Baxton family from Ohio City, Ohio wonder what became of G. C. Baxton, born about 1830? He died – somewhere on the plains – 24 June 1852.[2] I tried to find the back story on some of the faceless names from the column, searching 1850 census records to see if I could identify any of those who had a specific location and an age associate with their names. Sadly, I struck out on the handful I investigated. But a Google search led me to David J. Langum’s “Pioneer Justice on the Overland Trails” with more news about two of those 250 deaths in the 1852 newspaper - T. Miller’s and Lafayette Tate.[3] T. Miller, (unnamed in Langum’s article,) was a cattle overseer in the Brown emigrant party who fought with one of the drivers by the name of Tate. The driver's brother, Lafayette Tate, 19, ran up, stabbed Miller in the back, then slit his throat. Based on multiple diary accounts cited by Langum, we learn about the speedy frontier justice – with quickly assembled jury, judge, prosecutor and defense counsel. Witnesses were examined, Tate was found guilty and thirty minutes later hanged. According to the diaries Langum cited, the brother who originally fought with Miller was allowed to continue on with the company. For those interested in more about pioneer justice on the trails, be sure to read Langum’s article. But even for those whose relatives might have disappeared in a less dramatic fashion, I hope this post might inspire researchers to not stop at just the local paper in their ancestral locations, but consult even far-off papers for details on their families’ lives. [1] “Deaths on the Plains this Season,” Sacramento Daily Union, 2 November 1852, p. 2, col. 5; digital image, California Digital Newspaper Collection (www.cdnc.ucr.edu : accessed 7 July 2020). A search on The California Digital Newspaper Collection for “death on the plains” led to other articles in Sacramento and San Francisco newspapers, some of which were repeats of each other. [2] “Death on the Plains this Season.” [3] Langum, David J. "Pioneer Justice on the Overland Trails." The Western Historical Quarterly 5, no. 4 (1974): 421-39. Accessed July 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/967307.

2 Comments

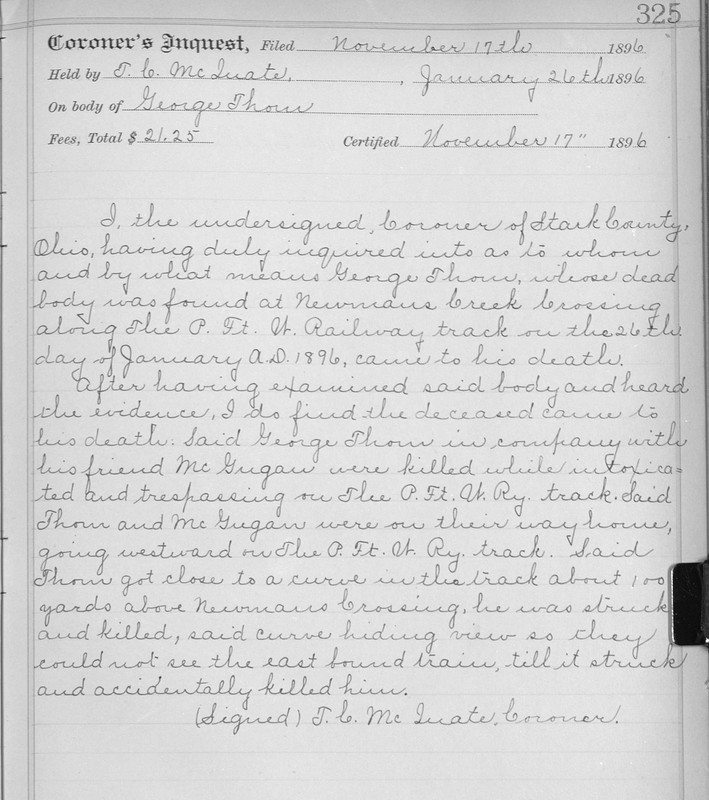

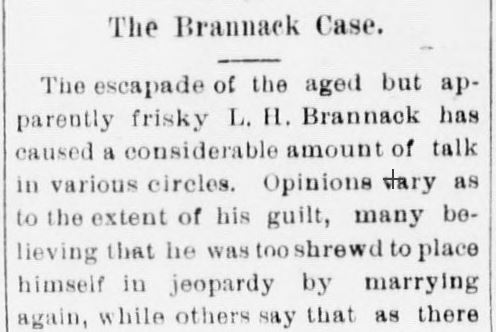

In my latest post on the Julia Achard story, “Julia Achard and the Death of Sarah Ahern,” I quoted from some coroner’s inquest records. Are you using coroner’s inquests to fill in your family history? If not, maybe you should be. If a decedent’s death was under “suspicious” circumstances, a coroner may have been called in to investigate. “Suspicious” could mean some sort of accident, a suicide, or an unattended or unexpected death. The coroner may eventually deem that the unexpected death was due to natural causes, but if the decedent had not been under a doctor’s care, or recently seen by a physician, there might be some question as to the cause of death and require a coroner’s investigation in the matter. Where can you find coroners’ records? You can contact the county where the death occurred to see if there was an inquest. The coroner might be a branch of the sheriff’s department or might have an office unto itself. When in doubt, do a little digging on the internet, or contact the county sheriff and they can point you in the right direction. Some coroner’s records are available on FamilySearch. Do a “Place search” in the catalog for the county and state of interest https://familysearch.org/catalog/search). In the catalog section under “Vital records” for that county, you might find “Coroner’s records” listed. Stark County, Ohio is one place that FamilySearch has made the coroner’s records available (https://familysearch.org/search/catalog/1922540?availability=Family%20History%20Library). When looking at on-line records, you may find that some of the pages have been blacked out due to privacy restrictions. What might prompt a researcher to look at coroner’s records? Sometimes the death certificate might indicate if there was an autopsy done. A coroner’s report might provide more details. Or maybe you found a newspaper article about the death which hints at an accident, a suicide or something otherwise suspicious. A newspaper article might even mention that a coroner's inquest would be held. Or maybe the only death “certificate” you can locate is a line item in a death register, where the “Cause of Death” column notes “blood poisoning” or “RR accident.” Though the term "R.R. Accident" might seem self-explanatory following up with a coroner’s report can give you many more details of just what happened. And if you find a young woman died of blood poisoning, you'll definitely want to look for coroner's records - many of these cases, were similar to the story of Sarah Ahern, the result of an illegal operation to terminate a pregnancy. Some coroner’s reports are more extensive than others. I’ve seen some one-page pre-printed, fill-in-the-blank forms and at the other end of the spectrum, some six-page or longer reports which include transcriptions of the testimonies of several witnesses. But with each one, I came away with more details about the death I was researching. Here’s one example… I found a brief article on Newspapers.com in The Akron Beacon Journal of 27 January 1896 indicating Andrew McGowan and George Thorn were killed by a train on the Fort Wayne road near Massillon, Ohio.[i] I was able to find their death records on FamilySearch.[ii] For each man, the ledger-style death record showed the cause of death as “R. R. Accident.” But from the coroner’s records, many more details come to light regarding the death of “George Thorn, whose dead body was found at Newmans Creek Crossing alonth The P. Ft. W. Railway track on the 26th day of January A.D. 1896…” Coroner T. C. McQuate states that after examining the body and heard the evidence “I do find the deceased…George Thorn in company with his friend McGugan were killed while intoxicated and trespassing on the P. Ft. W. R. track. Said Thorn and McGugan were on their way home, going westward on The P. Ft. W. Ry track. Said Thorn got close to a curve in the track about 100 yards above Newmans Crossing, he was struck and killed, said curve hiding view so they could not see east bout train, till it struck and accidentally killed him.”[iii] McQuate reports much the same regarding the death of “Auda McGugan.”[iv] As you can see, the coroner’s report provides significantly more detail than the “R.R. Accident” noted in the death register. If you haven’t used coroner’s records in your genealogy research, it might be time to have a look at some! [i] “Miners Killed,” The Akron Beacon Journal, 27 January 1896, page 3, col 1, from Newspapers.com, accessed 5 March 2017 [ii] "Ohio, County Death Records, 1840-2001," database with images, FamilySearch.org. (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89ZR-VGKJ?mode=g&cc=2128172 : accessed 5 March 2017), Thornton, Geo. W, 26 Jan 1896; citing Death, Newman, Lawrence Township, Stark, Ohio, United States, source ID v 3 p 534, County courthouses, Ohio; FHL microfilm 897,621 AND "Ohio, County Death Records, 1840-2001," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F665-QQS : accessed 5 March 2017), Andrew Mcgougan, 26 Jan 1896; citing Death, Newman, Lawrence Township, Stark, Ohio, United States, source ID v 3 p 376, County courthouses, Ohio; FHL microfilm 897,621. [iii] "Ohio, Stark County Coroner's Records, 1890-2002," images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9GKR-X9N?cc=1922540&wc=SNB8-SPJ%3A218158301 : 21 May 2014), > image 172 of 209; County Records Center, Canton. [iv] "Ohio, Stark County Coroner's Records, 1890-2002," images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GGKR-X51?cc=1922540&wc=SNB8-SPJ%3A218158301 : 21 May 2014), > image 174 of 209; County Records Center, Canton. Last we saw of Lyman Brannack, he had recently settled a law suit in Santa Cruz, California. To catch up, see my blog post, 'Here a Court Case, There a Court Case. Shortly after he settled a lawsuit in Santa Cruz, Lyman decided to take a trip to Pontiac, Michigan, perhaps to see family. In any event, while he was there, he met a Mrs. Hagerman and after a whirlwind courtship they decided to get married, notwithstanding his marriage to Sarah. They were to have been married in Pontiac, but were worried about Mrs. Hagerman’s former husband, so they stole away and were married at Niagara Falls.[1] They left for England. It was there that the new Mrs. Brannack learned that her husband had a legal wife in California. Upon her return from England, she writes to James Briggs, a friend of Lyman Brannack from Santa Cruz: "Mr. James Briggs, Most Respected Sir. – It is with humility and under the most painful circumstances that I attempt to address you as I am the lady upon which Mr. L. H. Brannack practiced so much deception. I married Mr. B. in good faith that he was all he represented himself to be. I was wholly innocent in this matter and while I feel most deeply humiliated yet I committed no sin or crime. "I had been, as I supposed, his legal wife just four weeks to a day, when a letter came from my dear children informing me of the fact that Mr. B. had a living wife. I asked him if the statement were true and he said it was. I never lived with him another hour as his wife after that, but immediately acted upon the advice of my dear daughter and sailed alone by first homeward bound steamer for New York. While I greatly deplore the step I took, yet I feel that I was not to blame. I am very proud and my family has ever stood above reproach and we feel all this very keenly. It has subjected me to much newspaper notoriety which is very mortifying to us all. I feel very sorry for all Mr. Brannack’s people, especially his present wife and his children. It is a most lamentable thing all around. I have returned to my own city and my many friends who crowd around me and say “You have our sympathy, we know you were not to blame.” Now Mr. Briggs, Mr. Brannach told me to write to you and ascertain from you what his reputation and standing had ever been in Santa Cruz, and where he had lived. Of course, after Mr. B. had so grossly deceived me I could not place much confidence in anything he told me and he referred me to you. Did Mr. Brannack own certain property in Santa Cruz, some lots described as follows? "Now, Mr. Briggs, I wish to know if Mr. Brannack was the bona fide owner of these lots when he left Santa Cruz for his trip to Europe and if he still owned them up to July 1st, 1889, and if there was any incumbrance [sic] on the same, and will you please give me your estimate of their value. Mr B. told me to write to you as soon as I arrived home, and said you would give me any information I might wish concerning him. How much is Mr. Brannack considered worth as to property? Please make immediate reply, as I am very anxious to know. Respectfully yours, Frances M. Hagerman[2]" While the former Mrs. Hagerman is “deeply humiliated” she’s also quite curious about just how much money she might have come into on her marriage to the deceptive Lothario whom she wed so quickly. In fact deeds sent by Mrs. Hagerman to the Santa Cruz County Clerk were filed on 24 July 1889. They were deeds for two pieces of property from Lyman Hibbard Brannack to Frances M. Hagerman, dated July 1, 1889 and were made in the city of London, England, describing property in Santa Cruz including several lots in one area, as well as another parcel with a house and improvements. According to the paper, “the entire property deeded by Brannack to Mrs. Hagerman is worth from $2,500 to $3,000. [3] The legal Mrs. Brannack had filed for divorce when she determined that Brannack did apparently go through with the marriage to Mrs. Hagerman.[4] In late August, Mrs. Hagerman-Brannack traveled to Santa Cruz to see “her” property. She sat down for an interview with The Daily Surf, and bore a letter from her attorneys in Michigan, supported by the signatures of many leading citizens of Pontiac. Interestingly, the supportive letter notes that she had been married to Francis Hagerman for a number of years until he became intemperate and abusive of her, but fails to mention that she had spent a term at the Kalamazoo Insane Asylum (where she was at the time the 1880 census was taken) and lectured publically about her time in the asylum.[5] In October, Mrs. Sarah Brannack was granted a divorce on the grounds of bigamy. Mrs. Hagerman relinquished all the deeds to property in Santa Cruz and returned to Michigan.[6] It does not appear that Lyman Brannack returned to the United States, preferring to remain abroad rather than face bigamy charges. Mrs. Sarah Brannack was not quite done with her husband’s family when she received a good portion of real and personal property in October of 1889. In March of the following year, she was sued by Mrs. Sarah A Clapp, Lyman’s daughter, for some personal property. It seems that Lyman Brannack induced Thomas Clapp, Sarah’s husband, to leave a lucrative situation in Tulare county and make his home in Santa Cruz with his wife. Brannack gave the property involved, a stationery engine, two wagons, a buggy, two horses, harness, etc and a colt to Sarah Clapp. Sarah Brannack had received this property originally as part of her divorce settlement from Lyman, but the judge in Clapp v. Brannack ruled in favor of Mrs. Clapp. The paper lamented that the family’s dirty linen was taken to Court to be washed.[7] More next week - Like Father, Like Son - Julia's brother Charles Brannack has problems of his own.... [1] The Daily Inter Ocean, 23 July 1889 “She Married a Married Man” [2] Santa Cruz Daily Surf 26 July 1889, page 3 “Brannack’s Badness” [3] Santa Cruz Daily Surf 25 July 1889, page 3 “Brannack’s Benevolence” [4] Santa Cruz Daily Surf 27 June 1889, page 1 [5] Santa Cruz Daily Surf 5 June 1889, page 3, “Brannack’s Bigamy”; 1880 US Census Year: 1880; Census Place: Kalamazoo, Kalamazoo, Michigan; Roll: 586; Family History Film: 1254586; Page: 199A; Enumeration District: 134; Image: 0399, line 46 [6] Santa Cruz Daily Surf 9 Oct 1889 [7] Santa Cruz Daily Surf 9 Oct 1889, 21 March 1890, page 3 |

AuthorMary Kircher Roddy is a genealogist, writer and lecturer, always looking for the story. Her blog is a combination of the stories she has found and the tools she used to find them. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|