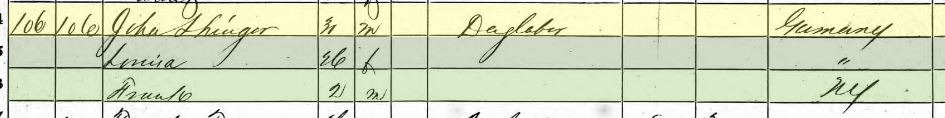

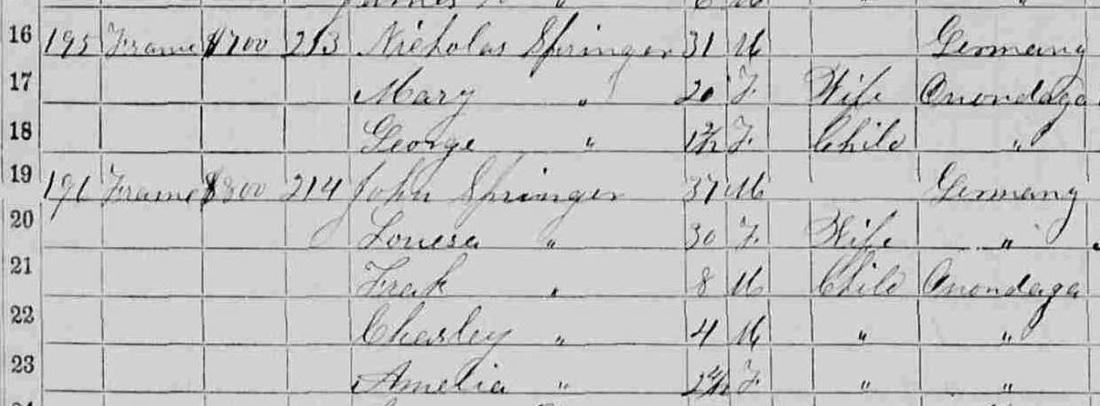

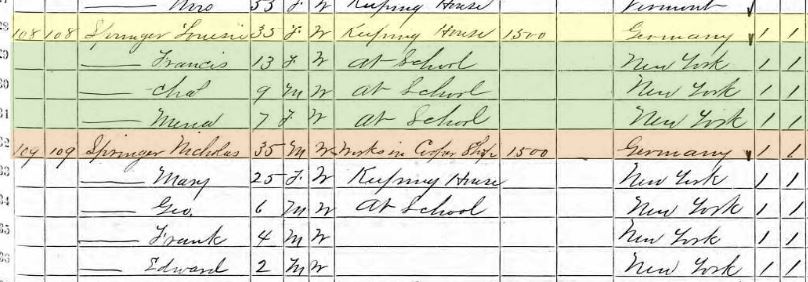

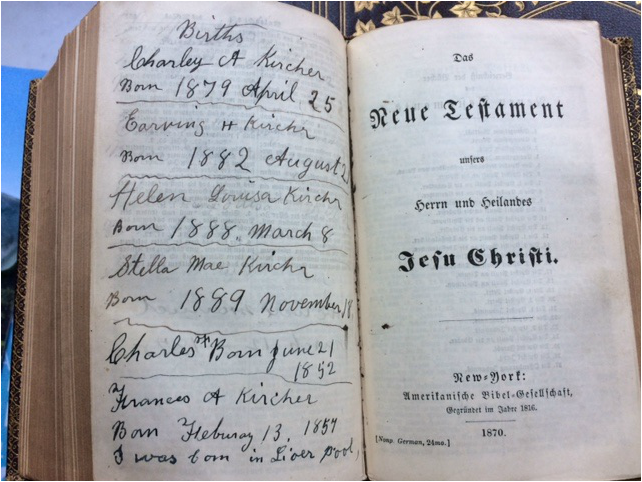

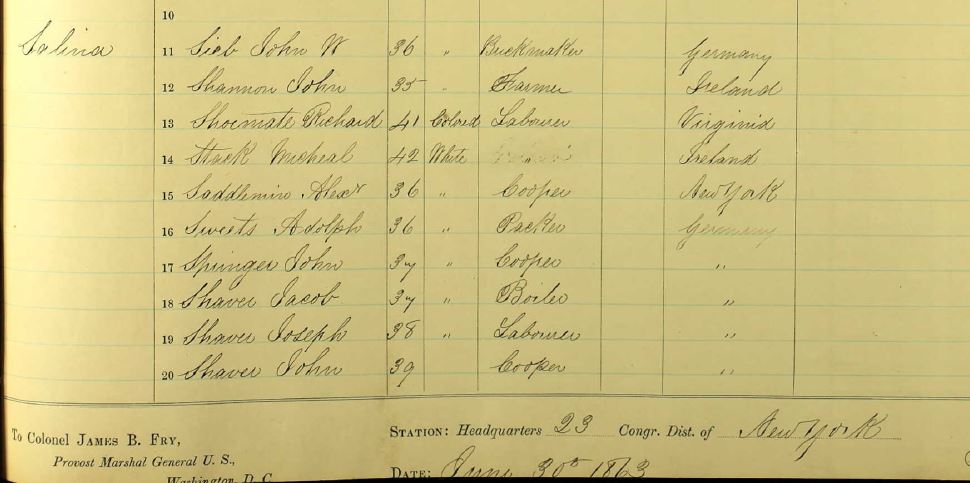

Page from the bible given to Frances Springer Kircher by her mother Page from the bible given to Frances Springer Kircher by her mother When you’re looking for someone on the census, and you can’t find them, but you know they MUST be there, be willing to expand your search a little. You can expand the age range. You can expand the geographic parameters. And maybe, when all else fails, try to expand your gender possibilities. Such was how I finally found my great-grandmother, Frances Springer. I was pretty sure the family had to be in Onondaga County. The record in her bible said that my great-grandmother, Frances Abelone Springer was born in Liverpool, New York on 13 February, 1857.[1] Her father’s Civil War draft registration from June, 1863 indicates he was living in Salina, Onondaga, New York. The family should be pretty easy to find on the 1860 census, right?  Civil War Draft Registration, Salina, Onondaga, New York for John Springer Civil War Draft Registration, Salina, Onondaga, New York for John Springer Part of my problem might have been the names and the date of death for Johannes. The family genealogy done by a distant cousin (not sourced, of course) showed my great-great grandfather as Johannes Springer, born 1835, died Oct 3, 187_ at age 42, married to Louisa Caroline Hartman, born June 3, 1836. And I think at one time I had heard that my great-great grandmother was known as Caroline (but in retrospect, I think I must have been under a wrong impression. My bad.) In any event I looked for Johannes and Louisa and their daughter, Frances, in the 1860 and 1870 census, and try as I might I couldn’t come up with the family. But then I found the Civil War registration for John Springer[2], and I knew they had to be somewhere in Onondaga County, so I expanded my search. Often when I can’t find a family in the census under the parents’ details, I look for the children. There are several reasons this trick works for me. For example, an adult of age 30-ish could “look” somewhere between 25 and 40, a 15 year spread. But a three year old child is not likely to be listed as age 1 or age 10. She might show up as age 2, 3, 4 or maybe 5, a considerably more precise age than her parents. Place of birth is easier to pin down, as well. Perhaps the parents were born in “Germany.” But the census might show Bavaria, Hannover, Germany,… who knows. But with the child who is only 2 or 3 years old, she is likely - not certainly, but likely - to be living near where she was born, and appear on the census with a birthplace near where she was living. So if I know my great-grandmother was born in Liverpool, NY in 1857, she’s probably going to show up as born in NY on the 1860 census. So I begin to look for a 3-year-old girl, Frances Springer and there are none to be found in Onondaga. OK, maybe try the middle name, Abelone. Maybe she’s Abby or some variant. Nope. But… but… but, they HAVE to be there (says the genealogist, stamping her foot!) So… maybe Johannes is something else… hmmmm…. John? And could I let go of the “Caroline” and try Louisa? In 1860 I did find a family, John and Louisa, both born in Germany, and their 2-year-old son, Frank.[3] A son. Not my family. Then I checked the 1865 New York state census. John and Louisa Springer, both born in Germany, and now three children appear – sons, Frank and Charley and daughter, Amelia.[4] My great-grandmother had a brother, Charles, and a sister, Amelia. This is looking more like my family, but my great-grandmother is still a boy. Interestingly, the household enumerated immediately prior to John and Louisa on the 1865 census is headed by a Nicholas Springer, born in Germany. And finally, on the 1870 census, Louisie Springer is the head of household (that family genealogy I talked about earlier was wrong – John died in 1864)[5] with her three children. Nicholas Springer, again, is right next to her on the census. And her children are now two daughters, Francis and Mina (Amelia) and only one son, Charles.[6] Why all the confusion? Maybe my great-great grandmother told the census taker her child’s name was Franke in her German accent, and the enumerators assumed Frank must be a boy. I don’t know… but I’m glad she finally turned out to be a girl, because otherwise, I wouldn’t be here to tell this tale. So, when you’re stuck and can’t find that family on the census… Hey, babe. Take a walk on the wild side. Maybe that she was a he. On the census, anyway. [1] Die Bibel, gift to Frances Springer from her mother, December 1872, in possession of Mary Kircher Roddy, Seattle, Washington

[2] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Consolidated Lists of Civil War Draft Registration Records (Provost Marshall General’s Bureau; Consolidated Enrollment Lists, 1863-1865); Record group: 110, Records of the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau (Civil War); Collecioin Name: Consolidated Enrollment Lists, 1863-1865 (Civil War Union Draft Records); ARC Identifier: 4213514; Archive Volume Number: 3 of 3. Record for John Springer, 23rd Congressional District, Salina, Onondaga, New York. Accesses from Ancestry.com [3] Year: 1860; Census Place: Salina, Onondaga, New York; Roll: M653_829; Page: 99; Image: 18; Family History Library Film: 803829, household of John Springer, family #106 [4] "New York State Census, 1865," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVNJ-NRGX : accessed 13 July 2016), John Springer, District 01, Salina, Onondaga, New York, United States; citing source p. 29, line 19, household ID 214, county clerk, board of supervisors and surrogate court offices from various counties. Utica and East Hampton Public Libraries, New York; FHL microfilm 860,900. [5] FindAGrave memorial for John Sprenger, date of death 3 October 1864, Find A Grave Memorial# 23987756. [6] Year: 1870; Census Place: Salina, Onondaga, New York; Roll: M593_1061; Page: 622A; Image: 81217; Family History Library Film: 552560, household 108

0 Comments

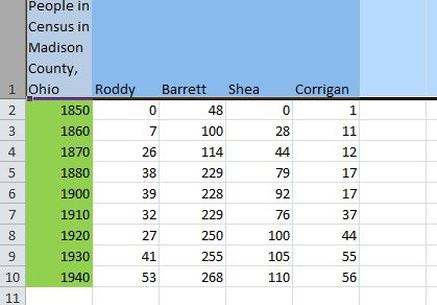

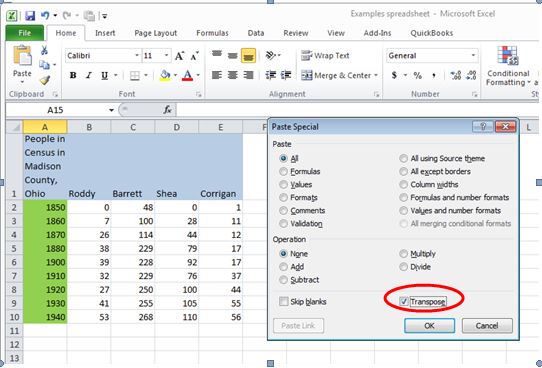

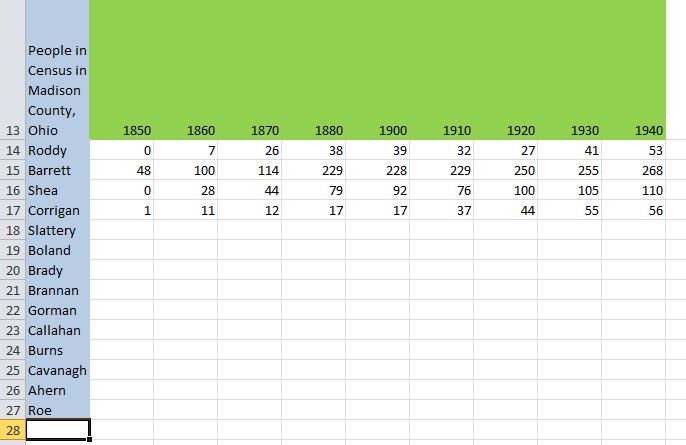

Ever create a spreadsheet, enter a whole bunch of data into it, and realize you set it up wrong? That It would be more useful and functional if the rows were columns and the columns were rows? Here is an example. Here I’ve created a spreadsheet to figure out how any people with various surnames lived in a community across various census years. I listed my nine census years down the left hand side to identify the rows, and I put my four surnames as the column headers. Looks great, but what happens when I find more names to research in that community? My table will just get wider and wider, but not get any taller (at least not until they release the 1950 census.) To my eye, short and wide tables just seem harder to read than tall and skinny ones. By this time I’m feeling a bit like a dodo. If only I’d used the census years (there’s a finite number of those) as the column headers and the surnames as the row titles. Do I have to retype the whole thing? Nope. I can transpose it. Here’s how… Highlight the table, in this example A1 to E10. Click Ctrl+C to copy. Click the cursor in a destination cell elsewhere in the worksheet or workbook (in this example I clicked in A13). Click on the triangle below the Paste icon, then click “Paste Special” and the box shown will appear. Click on the box next to Transpose. And here's what it looks like after, and I'm ready to enter more data! Easy peasy. A few simple steps and now my table looks just like I want it to. And without all that pesky retyping. Yay! Time for more research…

Before you begin to write your family story, go back and look at the records you have amassed. Look, for instance, at the census records, especially focusing on those columns over to the right. We look at name, age, and birthplace, but we tend to ignore those questions that might tell us more about their daily lives. Can she read or write? How many weeks was he out of work? A hundred years ago a man’s job was to support his family. How did he feel about himself in 1920 when he’d been out of work six months in the last year? How did his wife feel about him?

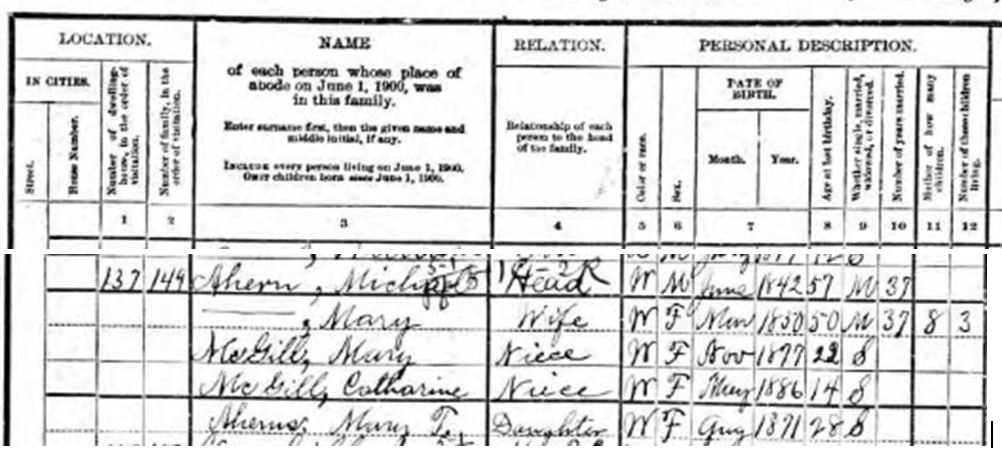

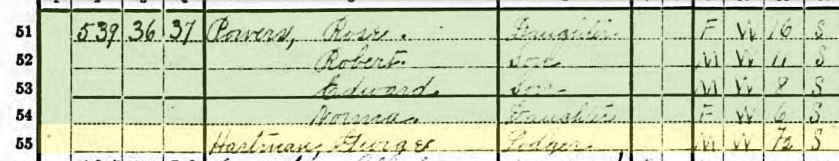

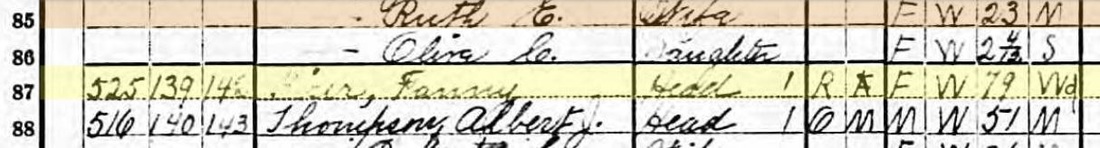

The 1900 and 1910 censuses asked about how many children a woman had and how many were still alive. Compare these answers to the other people on the page and to your ancestors or siblings. Your great grandmother gave birth to nine children and only two survived. How did she feel six months before the census, when Mrs. Moriarty next door brought home a baby girl to be spoiled by seven older brothers? What is her relationship like with her sister-in-law with so many healthy children? Take the time to compare your ancestor’s answers on the census to those of his neighbors. Consider the value of the assets he owns. Is he the only renter in the neighborhood? Is he the only recent immigrant in his neighborhood or is he one of dozens of immigrants? What is the ethnic background of most of the people in the locality? Imagine what dinner time might have smelled like in the Russian neighborhood your ancestor lived in. Wring every single clues you can find on the census to help tell your ancestor's story. Year: 1900; Census Place: Franklin, Somerset, New Jersey; Roll: 994; Page: 7A; Enumeration District: 0081; FHL microfilm: 1240994 Sometimes it is tempting to put in a birth year when searching for someone in a census. After all, if you know he was born about 1919, why wouldn’t you want to narrow the search? Well, including that might narrow your search results down to a big fat nothing! Here is an example from the 1920 census for the household of Robert Powers. Robert is listed along with his wife, Annie, and daughter, Caroline, on Sheet 2A with additional children Rose, Robert, Edward and Norma shown on Sheet 2B. Also living in the household is lodger, George Hartman. George is actually the illegitimate child of Caroline Powers, and perhaps the sensitive nature of his birth is why he is listed as a lodger and not a grandson. But look at George’s age. At first glance it looks like a “big” 7 followed by a 2. Many indexers have transcribed this as 72. But a more careful reading, combined with examination of the other ages written by enumerator, Mrs. M. K. Henderson, shows that for all the two-digit ages, both digits are written the same size. Mrs. Henderson does not tend to write one digit larger than another. Also, take a look at the fractional ages of the other young children. While some enumerators use a slash (/) between the numerator and denominator, Mrs. Henderson uses a dash (-). The 7 above the dash has melded into the 1 (of the number 12) below the dash, making it look like a large 7 (written with a mark across the 7) followed by a small 2. However, based on other numbers written by Mrs. Henderson, she does not tend to make her 7s with a mark across them, nor does she use an oversized 10s digit, as shown in the age of Fanny Gizer, aged 79. Mrs. Henderson has correctly listed George Hartman as age 7/12, and it is the transcription that is wrong.

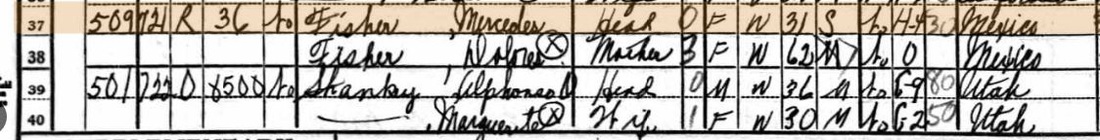

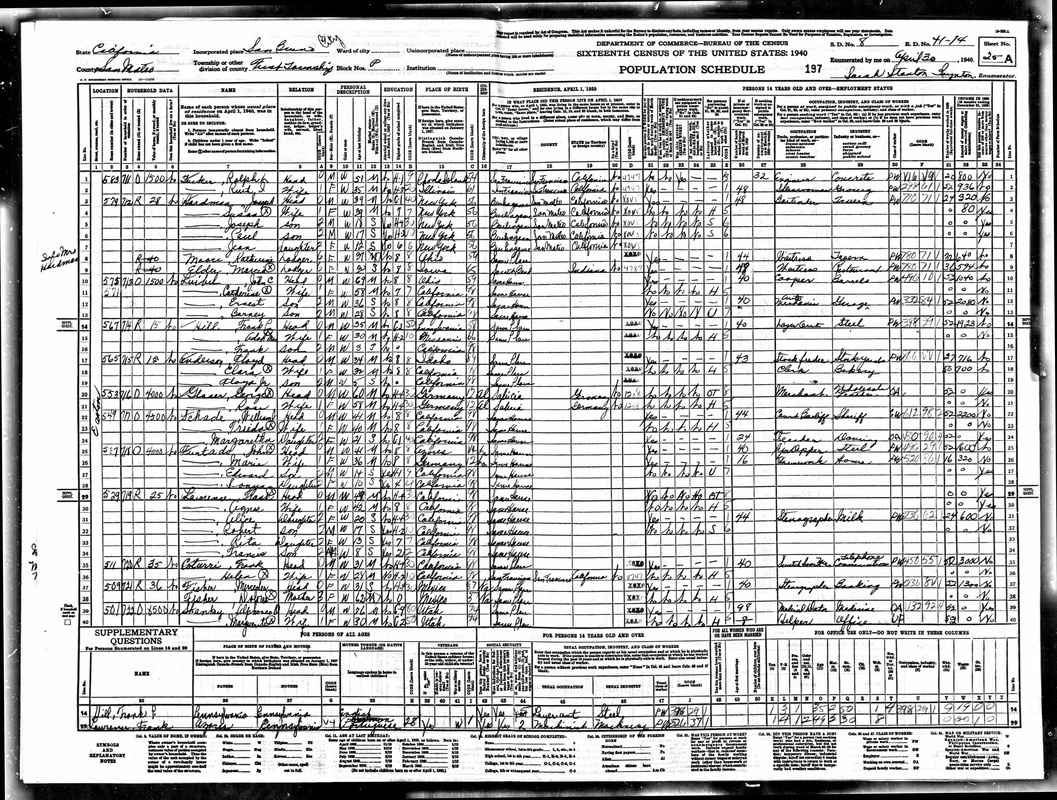

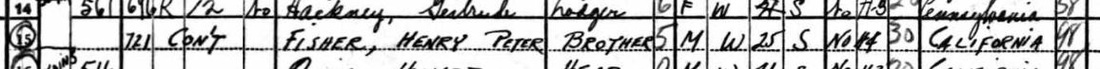

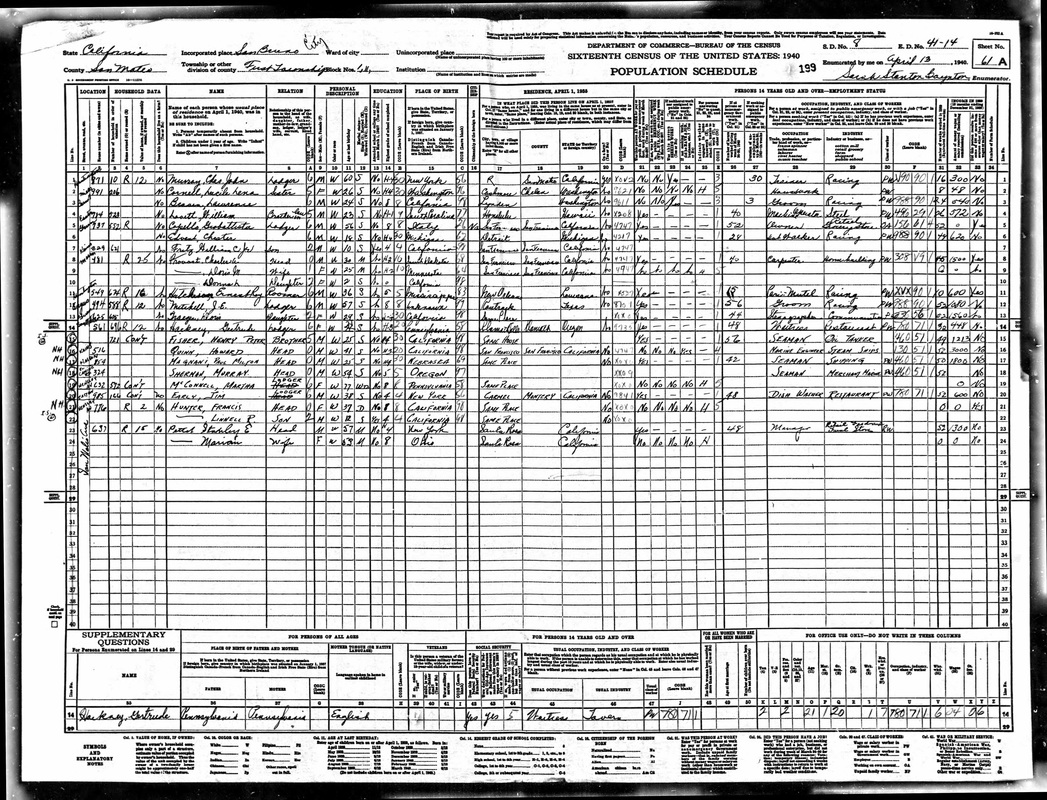

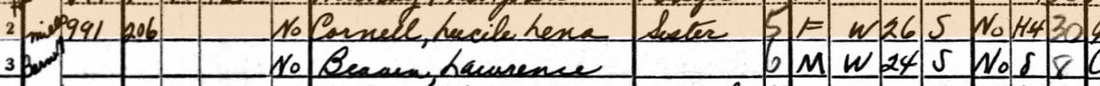

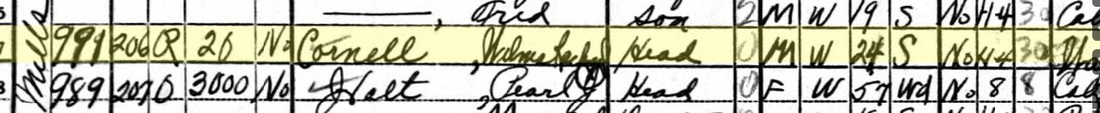

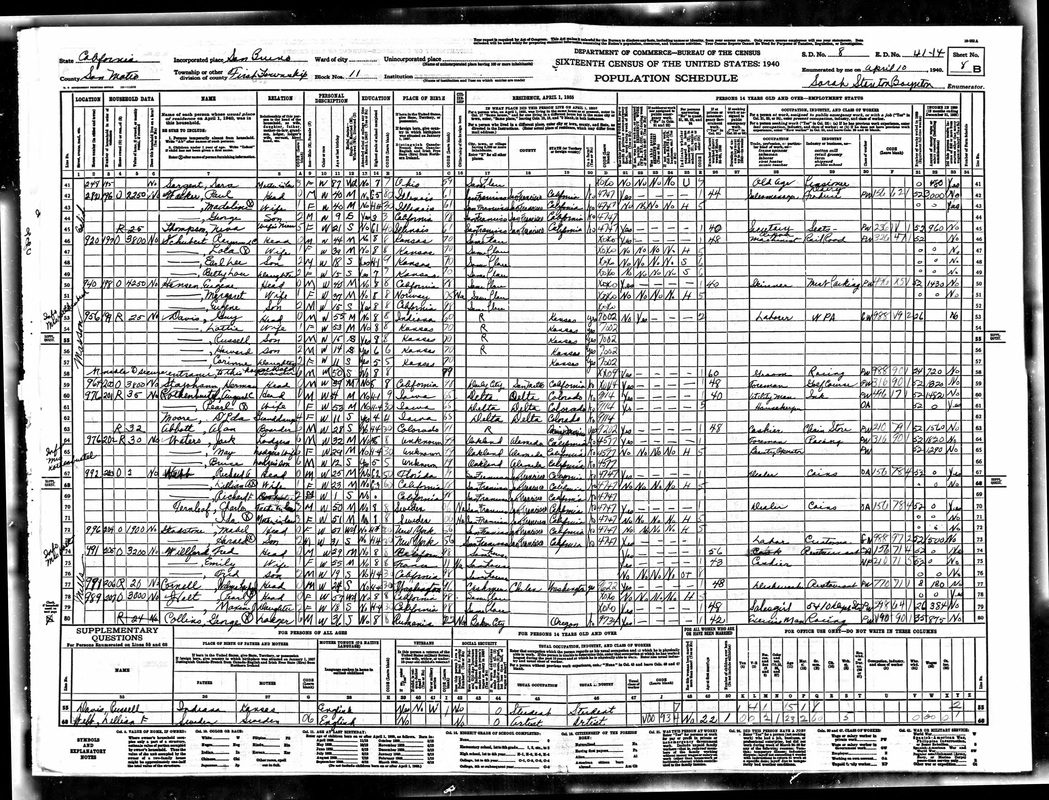

There are three take-aways from this exercise: 1) Be careful when entering a birth year to search for someone in the census that you don’t narrow your search parameters so much that you miss them all together. 2) Study the enumerator's penmanship to see how letters and numbers were written. 3) When you find an error in the transcription, notify the image provider. I have done this with both Ancestry.com and FamilySearch to make it easy for the next researcher looking for George to find him. I was searching for someone in the 1940 census in San Bruno, California and I noticed something odd. Partway down the page, the enumerator’s handwriting changed from cursive to block printing. It certainly got my attention and I’m glad it did. I learned a new trick. When you’re looking at a census for an enumeration district (ED), and you find the family you’re looking for, do you skip ahead to the last pages of the ED to see if there were other people in the same household that were listed on another page of the enumeration. Here’s an example from the 1940 census for San Bruno, San Mateo, California, ED 41-14, sheet 25A. On lines 37 and 38, residing at 509 Easton Street are 31-year-old Mercedes Fisher and her 62-year-old mother, Dolores Fisher. It was Dolores who provided the information. According to the number in column 3, this was the 721st household visited by the enumerator, Sarah Stanton Boynton. Since Ms. Boynton then moved on to enumerate household 722 at 501 Easton Street, you might have thought she’d listed everyone living at #509. Whoa. Not so fast there! Take a look at sheet 61A for ED 41-14.[1] There on line 15 is listed Fisher, Henry Peter, brother. No, he is not the brother to Hackney who appears just above him on line 14. He is the brother of Mercedes Fisher from Sheet 25A. How do I know this? Because in column 3 of Henry Fisher’s line, it says “721 Cont” meaning the continuation of household 721. Henry Fisher’s isn’t the only household continued on Sheet 61A. If you look at Line 2 on this page, you’ll see Lucille Lena Cornell, living at 991 Mills, visitation number 206. Go back to Sheet 8B, line 77, and you’ll find Lucille’s sister, Wilma Rachel Cornell, listed as the head of household. If you looked only at Sheet 8B you’d think Wilma lived alone and never know about Lucille. I can’t speak for every census, but I know this is not a problem peculiar to the 1940 census. I’ve seen similar “addendums” to households in the 296th ED in San Francisco in 1900.[2] Word to the wise – always remember to check the last few pages of an enumeration district to see if any additional household members are hiding there.

This is just one of the 20+ tips in my Censation Census Strategies talk. I’ll be presenting it at the 2016 Northwest Genealogy Conference in Arlington, Washington on August 18th. I hope to see you there. [1] Ancestry.com shows 55 images in ED 41-14. The images are in sets of two, an A and a B sheet, Sheets 1A-15B are images 1-30 in the set. Sheet 15B is appears again as image 31. Images 32-53 are labeled as Sheets 16A-26B. The final 2 images in the set, 54 and 55 are Sheet 61A and 61B. [2] 1910 US Federal Census for California, San Francisco, San Francisco, ED 0296, Sheet 8, lines 29-32, Pope family, (Ancestry.com image 15 of 21) and 1910 US Federal Census for California, San Francisco, San Francisco, ED 0296, Sheet 11, lines 29, Sydney Pope (Ancestry.com image 21 of 21) Sometimes finding someone on the census is easy, but often you need to strategize, be open, and hope for a little luck.

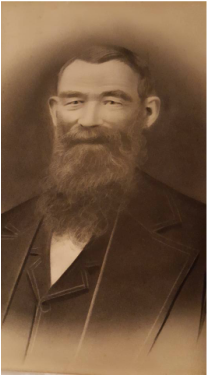

The census images we look at today are not the original working copy of the enumerator. After a day in the field, knocking on doors and collecting information, the enumerator sat down and copied the data onto the final forms to be turned in. Perhaps it had been a long day, and the enumerator was a bit tired when he copied the names and details for the household of Douglas and Margaret Church onto page 31 for Sonoma Township, Sonoma, California of the 1870 census. He certainly appears to have been off a bit when he entered the information for lines 15 and 16 for James Church and Mary Laughlin.[1] Could it really be true that Douglas Church was born in Pennsylvania and his wife Margaret and their four-year-old daughter, Anna, were both born in California, but their son, one-year-old James Church, was born in England, and had a father and mother of foreign birth? Oh, and how about the tick mark in column 15 - that he attended school within the year? Little James must have been some Einstein! Either that or our census taker made a little booboo when he made his final copy. That error, mixing up a few tick marks and a birthplace, is what made it particularly troublesome for me to find Mary Lockren, already a difficult surname to search for. Poor penmanship aside, common spelling variants include Lockren, Lockran, Lochren, Lochran, Loughren, Loughran, Laughran as well as Locklin and Laughlin. Basically it starts with an L, has a hard C in the middle and ends in an N. After that it’s anybody’s guess. I knew from later census records that she was born about 1856 in England. As you can see from the census, using England as a birthplace, was most decidedly unhelpful in this case, so I did a simple search using just a name - “Mary L*N” - and an approximate age – 14. No birthplace. As a genealogist, it seems hard not to put in the information that I “know” is right. But sometimes less is more. And without that birthplace, Mary popped right up. A few pages away I found her mother, Anna “Locklin”, living in the household of James and Maria Kennedy.[2] Digging a bit further, I discovered Margaret Douglas was the daughter of Maria Kennedy.[3] Connection! And the Kennedys and Churches lived just over the hill from Anna Lockren’s sister, my great-great grandmother, Jane (Mary J) Ahern, in whose household lived one more “enumerator mistake” - Anna’s son, Charles “Lucking.”[4] Yep, sometimes the census taker was wrong, and it takes a little more than “luck” to connect the dots – try a less is more strategy. [1] Ancestry.com. 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. Year: 1870; Census Place: Sonoma, Sonoma, California; Roll: M593_91; Page: 446A; Image: 459; Family History Library Film: 545590 [2] Ancestry.com. 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch Year: 1870; Census Place: Sonoma, Sonoma, California; Roll: M593_91; Page: 443A; Image: 453; Family History Library Film: 545590 [3] http://worldconnect.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=wjhonson&id=I273 [4] Ancestry.com. 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. 1870; Census Place: Vallejo, Sonoma, California; Roll: M593_91; Page: 456A; Image: 479; Family History Library Film: 545590  James Ahern circa 1870 (Original charcoal portrait from the collection of Danni Chambers Meisinger) James Ahern circa 1870 (Original charcoal portrait from the collection of Danni Chambers Meisinger) I recently presented my “Where There’s a Will There’s a Way…” lecture to the Belfair Chapter of the Puget Sound Genealogical Society. Here’s one of the stories I shared. In 1873, my great–great-grandfather, James Ahern, suddenly found himself a 42-year-old single father with a house full of children. His wife, Jane, died delivering baby number six.[1] James died 25 years later but never remarried. For a man in that day and age, a farmer with not only six youngsters to raise but a 160-acre farm and a barn full of dairy cattle to tend to, it’s quite unusual to not have found a helpmate to marry. But research into the will of his next-door neighbor shed a little light on how he might have managed to get his kids raised without taking another wife. The 1880 census begins to tell the tale. James appears with his six children, from Mary Agnes, age 20, down through Henry, James, Sarah, and Jane to John C, age 7.[2] I think Mary Agnes was probably pretty capable of taking on much of the responsibility for her younger siblings. She was 14 when her mother died, and she went on to raise a large family of her own. Right next door are Isaac and Mary Ingram.[3] Isaac and Mary had no children of their own. But on October 20, 1871, Isaac and Mary served as godparents to Jane Isabella Ahern,[4] so clearly the Ingrams had a close relationship with the Aherns. I can see among the farmhands living with the Ingrams in 1880 is one Patrick Bradley, a 32-year-old Pennsylvanian. About a year and a half after that census was taken, Mary Agnes Ahern married Patrick.[5] I can just see Mary Ingram finding excuses to fix these two up – “I baked a cake, Patrick, why don’t you take it over to the Aherns?” Just on a hunch, when I was visiting the courthouse in Santa Rosa, I looked up Mary Ingram’s will, and in it I found a few more details to confirm my theory that Mrs. Ingram likely played a pretty active role in the lives of the motherless children next door. She had three nieces and a nephew who were remembered in her will with specific bequests of $1000 each and additional named beneficiaries included “my friend Lizzie Bradley” (Patrick and Mary Bradley’s oldest daughter) who was bequeathed $200, “my friend Mary Bradley,” given $200, and “my friend Sarah Ahern” who was given $100. Once the specific bequests were made and the final expenses paid, Mary divided the residuary of her estate two-ninths to each of her nieces and nephews and one-ninth to Lizzie Bradley.[6] Lizzie was deaf, and perhaps this disability led Mary Ingram to be particularly generous toward her. Wondering about how it was that a widower with a whole passel of children could manage to survive without a wife… imagining what kind of an influence Mary Ingram might have had in bringing lovebirds Patrick and Mary together… these thoughts led me to look for the will of my ancestor’s neighbor. I don’t think many genealogists have the next-door-neighbor’s will on their list of “must get” documents, but I’m glad I thought to put it on mine! [1] Sonoma County California death records, 1873-1890, Volume 41, page 1, Jane Aheran, October 9, 1873 [2] US Federal Census Year: 1880; Census Place: Vallejo, Sonoma, California; Roll: 84; Family History Film: 1254084; Page: 23D; Enumeration District: 121; Image: 0049 [3] ibid [4] Baptismal records of St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church, Petaluma, Sonoma, California [5] Marriage records of St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church, Petaluma, Sonoma, California [6] Sonoma County, California Record of Wills, Volume J, page 252 |

AuthorMary Kircher Roddy is a genealogist, writer and lecturer, always looking for the story. Her blog is a combination of the stories she has found and the tools she used to find them. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|